I’m not a lawyer—but I have read Andrew Branca’s book (you can get a free copy by following the link) and several others. I’m not an expert either, but this series is meant to help you start understanding legal concepts and realities so you can seek out deeper knowledge for yourself.

Ultimately this is not legal advice, you should seek out a qualified attorney in your area and see guidance from them!

Despite what you might see online, claiming “self-defense” isn’t as simple as saying “I feared for my life!” on the stand. In reality, it’s a minefield of legal nuance—and one misstep can change everything.

Misconceptions and My Early Mistake

When I first started looking into self-defense law, I ran into acronyms like IMOP:

- Intent

- Means

- Opportunity

- Preclusion

I assumed that if I could check those boxes, I was covered. But that turned out to be an oversimplification. A kind comment (I think from Andrew Branca himself) on an old blog post of mine pointed out how tricky a self-defense claim can be in real life. That moment pushed me to dive deeper.

The truth is, the legal system doesn’t start from a place of perfect knowledge. The responding officer almost always misunderstands what actually happened. Screaming “It was self-defense!” doesn’t help—especially when what really happened was someone’s ego (their “Monkey”) escalating things into a preventable fight.

And let’s be honest: a career criminal might be better at looking innocent than you are at being innocent.

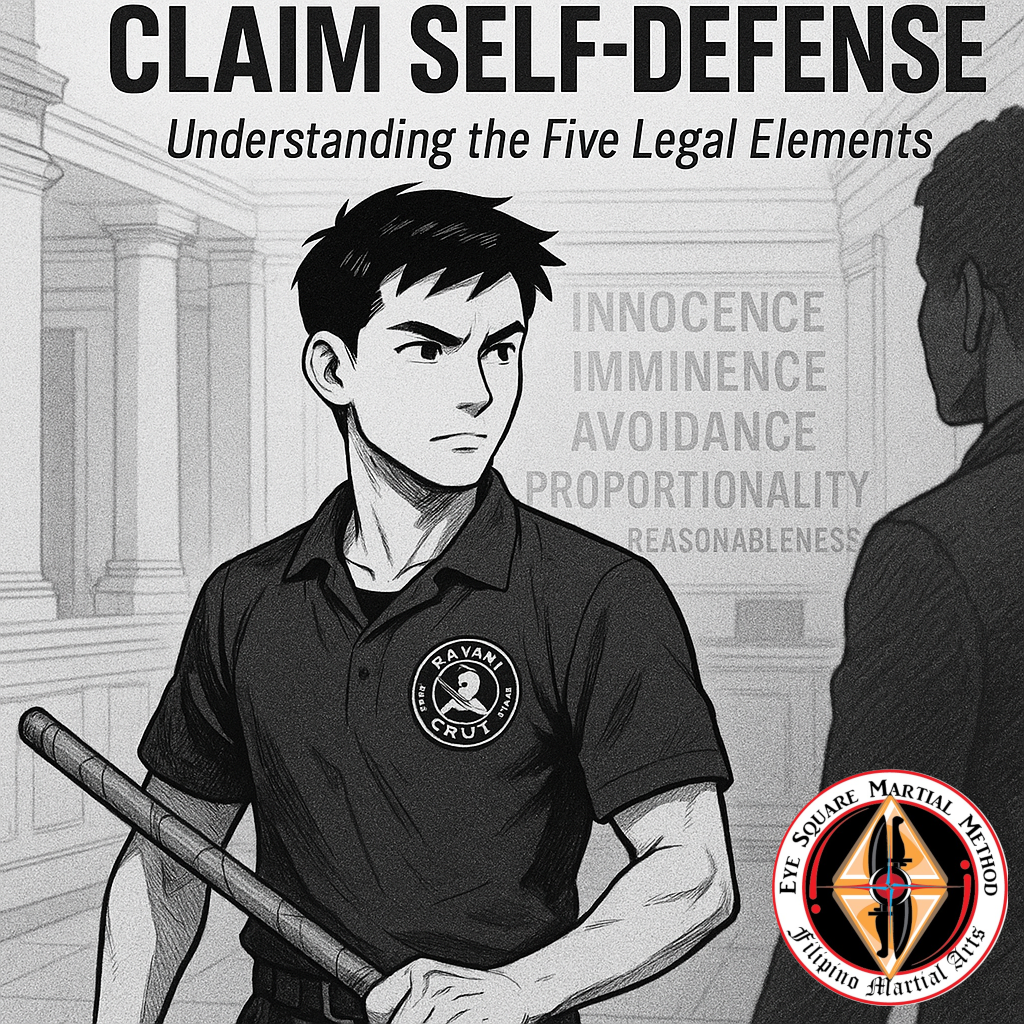

Branca’s Five Elements of Self-Defense

To navigate this legal minefield, Andrew Branca presents Five Elements of Self-Defense. These are legal standards—not gut feelings—and learning them helps you understand when and how self-defense can be properly claimed:

- Innocence

- Imminence

- Avoidance

- Proportionality

- Reasonableness

Each of these words has a specific legal definition that doesn’t always match the casual way we use them in conversation. Let’s walk through each one.

1. Innocence

Were you the one who started the fight? Were you where you had a legal right to be?

If you’re engaging in threatening behavior—like squaring up aggressively, posturing, or hurling insults—you may lose your claim to innocence. There’s a legal concept called “Fighting Words”: if you provoke someone and they respond violently, the law may say you’re the aggressor.

2. Imminence

Imminence is about timing.

Was the threat right there, right then? Did they have the means and opportunity to carry out the threat immediately? Or was it more like “I’ll come back later!”

Example:

At a lacrosse game, an opposing player slashed a teammate of my brother. The player’s mom got angry and yelled at the coach, eventually threatening:

“Do you want me to get a baseball bat and beat the crap out of you?!”

Police were called. The officer asked if she had a bat. She didn’t. She’d have to go get one, come back, and then follow through. Since there was no imminent threat, no charges were filed.

3. Avoidance

Did you have a safe way to leave?

In many places, there’s a duty to retreat before using force, especially deadly force. The exceptions to this rule are legal doctrines like:

- Castle Doctrine (no duty to retreat in your own home)

- Stand Your Ground (no duty to retreat in public, under specific conditions)

Important note: these doctrines only relieve you of the duty to retreat—they don’t override the other four elements.

In some states, you may even have access to a Stand Your Ground hearing—a pre-trial hearing where a judge decides if the evidence supports your self-defense claim enough to block criminal charges or civil lawsuits.

4. Proportionality

Your response must match the level of threat.

If someone shoves you, that doesn’t give you the right to shoot them. But if someone comes at you with a knife, deadly force may be justified.

Context matters:

- A 5’3”, 105 lb woman being attacked by a 6’5”, 300 lb man may reasonably fear for her life even without a weapon being involved.

- The same goes for multiple attackers—even if none of them are armed.

This is called disparity of force, and it’s a key part of understanding proportionality.

5. Reasonableness

Would a “reasonable person” act the same way in your shoes?

That’s the million-dollar question, and it’s what jurors are asked to consider. Of course, jurors don’t know everything you did at the time. That’s why the defense must present:

- Prior history with the attacker

- Their reputation

- Any weapons present

- Training, physical limitations, or awareness on your part

- Distance and threat potential (e.g., knife at 10 feet)

The court weighs both subjective knowledge (what you knew) and objective standards (how a reasonable person would respond). Just saying “I was afraid” doesn’t cut it. You need to be able to explain why your fear was reasonable.

Wrapping Up

This was a denser post than usual—and with good reason. Self-defense law is full of complexity and myth. What we’ve covered here is from the defense’s perspective—what you need to justify your actions.

But self-defense claims don’t exist in a vacuum.

In the next post, we’ll talk about the prosecution—how they think, what they look for, and how they’ll try to dismantle your self-defense claim.

Leave a Reply